Counterintuitive Link to Building Occupancy, Energy Use

Click on the above link for the podcast version of the following interview.

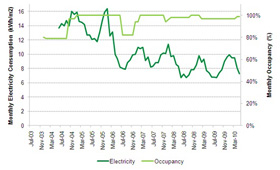

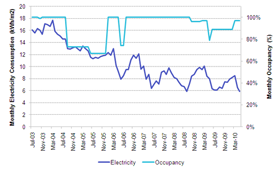

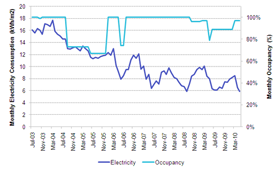

While it might seem that less people working in a commercial building means less energy used, data gathered by Sydney, Australia-based Investa Sustainability Institute shows that buildings actually perform better at full occupancy.

The goal of the research by Investa Sustainability Institute — the research arm of Investa Property Group, established in 2009 — was to create better buildings by making their operations more transparent, said Beck Dawson, sustainability manager at the institute.

Investa studies the aspects of building management that help people understand where energy has the most impact, she said. The study is part of the institute’s current Green Buildings Alive project, which provides an online platform for visualizing real building performance data and a discussion forum.

“If you think particularly about occupancy in theory, a building is only half full, maybe only half the floors are being used at any one time, so it should use less energy than another building that’s mostly or completely full,” Dawson said. “We’re just trying to understand, does it really work like that in practice? So we’re essentially using real data to try and understand some of these questions that might be self-evident or might not be, that help us understand how we can make them greener.”

“If you think particularly about occupancy in theory, a building is only half full, maybe only half the floors are being used at any one time, so it should use less energy than another building that’s mostly or completely full,” Dawson said. “We’re just trying to understand, does it really work like that in practice? So we’re essentially using real data to try and understand some of these questions that might be self-evident or might not be, that help us understand how we can make them greener.”While the research is based on just a snapshot of two buildings, the institute has seven years of data on 53 buildings that can be viewed through their Building Datalyzer tool.

The tool shows trends for emissions, energy, water, gas, complaints, occupancy and daily temperatures. These trends can be filtered by state, age, city, and occupancy, among others.

A building can input and view their own data trends, as well as view other buildings, to discover their own insight into the relationship between energy and occupancy, she said.

“In theory those should be linked, but in practice they’re not,” she said. “Because of the way building management systems run, especially in older buildings, you don’t have so much control to separate individual floors from the air conditioning system, for example. So in practice, although logically it makes sense, it doesn’t actually work that way.”

Dawson said that improved building design has led to more control over individual floors or areas of buildings.

“In the long run, a building that’s half empty should use half the energy,” she said. “At the moment, in practice, that’s not how it works.”

The study sample includes both old and new buildings in Australia, but the institute is inviting people from all over the world to input their data and make it available in a global portfolio.

“It’s definitely, especially relevant to people in the U.S. from the point of view that the more we can understand how to really drive the performance in the energy … the more we can share that same technology the world over,” she said. “There’s no reason why something that’s happening here can’t have direct relevance to a building in California.”

In addition to sharing data and starting discussions, the Green Buildings Alive project and the Datalyzer tool aim to create understanding of how people can better manage properties on a daily basis using real examples, she said.

“It’s quite interactive in the sense that people can play around with it and maybe find their own insight and try and understand what’s happening in a different building,” she said.

Dawson said building managers play a significant role in making big changes to buildings.

“It’s absolutely about the people around really understanding what they’re managing and being able to control it as much as they can,” she said, adding that being able to see a building’s operation more quickly — within hours, days or a week, for example — can improve performance.

“It’s not necessarily fancy technology, it’s just being able to access the things that are already happening in the building and then they’re able to better understand what time of day, what are things being turned on and off when they should be by the plant, etcetera,” she said. “All of it’s about just people very carefully more understanding what they’re doing and more carefully managing what they can control in buildings.”

Dimitris Kapsis, director of Energy Solutions at American Utility Management, said in his experience with commercial high rises like the ones in the study, energy efficiency depends largely on the type of building.

While the Oak Brook, Ill.-based utility management company serves multi-family residential properties throughout the country, Kapsis has worked in the commercial sector for more than ten years as a consultant.

“It appears that the buildings in the study are older buildings with central chillers,” he said. “The equipment has to run at 100 percent capacity even though the building might be half full.”

Buildings with older type of systems are required to maintain certain temperatures or humidity levels due to lease requirements, he said.

Kapsis said properties built in the last 15 to 20 years are the ones that have zonal air handle units to control specific floors or areas, which can make usage go down dramatically.

“Even at that level, the occupancy percentage and the energy usage percent is not directly proportional,” he said. “Just because you have only 50 percent of occupants, doesn’t mean you’re going to use only 50 percent.”

Older buildings at 50 percent occupancy might save only 10 percent, while newer buildings with zonal systems can drop energy use by 35 to 40 percent — though bigger savings still don’t make occupancy and usage 100 percent proportional, he said.

According to Kapsis, if the survey accounts for the difference in external weather conditions, the findings may be correct, but if they haven’t been considered the usage curve be almost solely based on weather fluctuation rather than occupancy.

“If the weather was colder this year, maybe that’s why the usage was higher, because it was colder,” he said.

Kapsis offered a number of possible ways to achieve energy efficiency, including upgrading or installing digital controls for temperature, or pressure, as well as monitoring temperature systems where the building is controlled a lot closer to where its supposed to be.

To improve building performance while still meeting law requirements on occupancy-based ventilation, Kapsis suggested monitoring carbon dioxide levels at strategic locations to capture how many people are in the building. He also said one can control outside air dampers rather than treat outside air.

“When it comes to a digital control system, instead of outdated pneumatic systems in buildings that are 30, 40, even 20 years old, you could get up to two to three percent savings just by replacing the controller so you have a lot more accuracy in the control of the building,” he said. “Old pneumatic controllers, they’re mechanical based and they tend to be out of calibration. They need to be adjusted one or two times a year.”

Kapsis said it is very important for the building engineer to know how the various systems are working together.

“Technology definitely assi sts in the energy management, but also, the staff has to be knowledgeable and react to different occurrences in the building,” he said. “So monitoring and controls are possibly 60 percent, possibly a little higher, and the knowledgeable personnel and also a very active preventative maintenance program such as replacing filters when they’re supposed to, making sure dampers work the way they’re supposed to … that’s the other 40 percent.”

sts in the energy management, but also, the staff has to be knowledgeable and react to different occurrences in the building,” he said. “So monitoring and controls are possibly 60 percent, possibly a little higher, and the knowledgeable personnel and also a very active preventative maintenance program such as replacing filters when they’re supposed to, making sure dampers work the way they’re supposed to … that’s the other 40 percent.”

sts in the energy management, but also, the staff has to be knowledgeable and react to different occurrences in the building,” he said. “So monitoring and controls are possibly 60 percent, possibly a little higher, and the knowledgeable personnel and also a very active preventative maintenance program such as replacing filters when they’re supposed to, making sure dampers work the way they’re supposed to … that’s the other 40 percent.”

sts in the energy management, but also, the staff has to be knowledgeable and react to different occurrences in the building,” he said. “So monitoring and controls are possibly 60 percent, possibly a little higher, and the knowledgeable personnel and also a very active preventative maintenance program such as replacing filters when they’re supposed to, making sure dampers work the way they’re supposed to … that’s the other 40 percent.”Within those percentages, managers must consider building occupancy levels, as well as the type of tenants in the building, he said.

“You might have a regular office building with regular office tenants, with laptops or computers and just regular office equipment, and you might also have technology-loaded offices, such as servers and computer rooms where you need supplemental cooling, that adds to energy consumption levels,” he said.

The timing of building occupancy can also lead to energy reduction through offbeat preheating or cooling, he said.

“We take into consideration a very hot August day where you expect 95 degree temperatures in the middle of the day — if you start your building (cooling) equipment at seven when occupancy starts, then you might be spending the entire day playing catch up and end up spending a lot more money,” he said. “If you start your building a couple of hours earlier and let it cool down before tenants come in, then you’re ahead of the game. During the peak hours where the energy is the most expensive, you can coast through those hours.”

Control systems that can forecast temperatures or use prior day temperatures to set a core temperature that only needs minor adjustment can also be helpful, he added.

“Having a robust control system, having a good preventative maintenance program in place, making sure your equipment is running, upgrading equipment as you move along with higher efficiency equipment, and lighting, will definitely provide substantial and noticeable energy saving,” he said.

The general theme of the survey did mirror the general trend of buildings decreasing energy consumption levels in the industry, said Ken Holiday, senior energy manager at Advantage IQ, a Spokane, WA-based facility information and expense management company focused on commercial buildings.

“The most important thing is that buildings are being run as they were designed to, and equipment that’s put in to a building is sized and spec’d according to anticipated building size and use,” he said. “It can be very important as months and years go by as equipment is changed over, maintenance has changed, and ultimately the building itself has changed.”

Holiday highlighted the importance of adjusting the operations of a building to fit those changes, adding that one effective way to do so is to re-commission the building.

“[Re-commissioning] essentially takes the current operations of a building, takes the current needs, and connects it so they’re aligned,” he said. “When that’s done it bridges the gap between the design intent of the building and the years that have passed, and the current operation.”

In terms of recent discussion on measured versus anticipated energy saving measures, Holiday said it’s important to understand how different energy-saving systems and operations interact to form the dynamics of a building.

“It’s hard to paint that whole landscape with one brush because different energy conservation measures will produce different types of savings and will make those estimates in different ways,” he said. “But one really important point is quite often multiple energy saving projects or energy saving opportunities will interact with each other.

In a large building, with 10 or 20 different energy conservation measures, the anticipated savings are not additive, Holiday said.

“If for example you have 15 different energy conservation measures, each is anticipated to have a two percent reduction in and of itself,” he said. “All combined, you’d certainly see savings.”

Holiday also noted that there are a few forces combining to make it easier for individuals and companies to reduce energy consumption, including more access to information on best practices and trained professionals, greater consciousness of the general public, finance options new products that enable smarter operations.

“We’re fortunate there’s a really strong movement to focus on energy consumption and identify opportunities to reduce that consumption,” he said.

David Pogue, the national director of sustainability a CB Richard Ellis — a national, full-service real estate company — said that although the company conducts various studies on their LEED and non-LEED commercial buildings, they had not previously looked at building occupancy.

“It stands to reason that you’re going to have a more efficient use because the energy being used is being used for purpose,” he said, adding that he was intrigued by the study and hoped to have his own staff run similar analyses.

Pogue said the company has found that almost any building can be improved without making changes to the physical plant.

“Most buildings are built better than they are operating, primarily because tenants have demands and managers and engineers will meet those demands,” he said. “Sometimes meeting a tenant demand means you don’t have the most efficient buildings.”

Pogue said that especially in the current low capital market, the company has worked on trying to get buildings to run the way they’re supposed to be run, and trying to get tenants to participate in the process.

“In the near term, I think there are a lot of savings to be gained by just running equipment better and getting engagement with occupants.”

Another study being conducted by the institute looks at occupant comfort inside commercial office buildings and its impact on energy use, taking into account how different times of the day or different external weather conditions can lead to better building management.

During Sydney’s recent bout of warm weather, the institute conducted a study where researchers monitored all occupants entering the building and whether they were wearing jackets or not. The study showed that if it was cold outside, many occupants entered the building dressed for the cool temperatures and found themselves to be too hot due to that expectation, Dawson said.

On hot days, not many people would come to work warm outerwear, but if the building had been cooled down, occupants would up feeling very cold, she said.

“The more we can understand the clothes people are wearing, for example, because it has an impact on their comfort, the better we can manage the building, and it might be that we make the building a little warmer to match that external temperature,” she said. “That might have a really profound impact on essentially how we manage buildings in the future — managing the comfort instead of managing the temperature, which is mostly what people and buildings do.”

Studies of occupant comfort levels are not well understood, but are becoming more common, according to Dawson. Comfort level studies can be difficult to conduct due to the amount of people necessary to get accurate results, and the time and money involved.

“Also, people aren’t terribly good at saying whether they’re comfortable or not. It’s one of those funny things where people are mostly saying, oh actually I’m a bit cold, but they weren’t thinking about it two minutes ago,” she said. “There are a lot of difficulties in measuring occupant comfort, but they’re increasing products in the market now that are starting to do that kind of thing and I think we’ll see more of that as time goes on.”

Dawson said the institute hopes people will become more transparent about their building performance.

“Those 53 buildings are a pretty good example. We haven’t seen that anywhere else in the world, whose made their entire portfolio available for everyone to look at,” she said. “People are often talking about commercial activity and that sort of data, but if we can’t share that sort of data, then we cant learn. People can share and understand better about how to understand how to be more environmentally friendly in their buildings.”

For more information visit www.greenbuildingsalive.com